The Digital Statement Part III

Image Restoration, Manipulation, Treatment, and Ethics

By Robert Byrne, Caroline Fournier, Anne Gant, and Ulrich Ruedel

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jeanne Pommeau and Julia Wallmüller along with the FIAF Technical Commission members for their valuable insights and suggestions.

This section of the Digital Statement describes the ethical principle[1] and general guidelines related to motion picture restoration. The discussion is illustrated with a variety of typical cases, but the authors recognise that all projects are unique and that no single document can comprehensively address all the challenges or circumstances presented by any given project. For this reason, the reader is encouraged to focus more on the principles and less on specific technical details. Digital technology is constantly evolving and, while certain aspects of this paper may eventually become obsolete, the foundational philosophy and principles of ethical film restoration should remain unchanged.

DIGITAL RESTORATION

Prior to the development of digital image technology, the toolset available to film restorers was generally limited to what could be achieved through photochemical means. Film materials could be physically cleaned to remove dirt, and the appearance of scratches could be reduced through the use of wet-gate duplication. Colour could also be adjusted through grading (timing), and the Desmet Method could be used to approximate the tints and tones of silent- era films. If new elements, such as titles, had to be recreated, they were photographed, printed, and physically inserted into the new negative or print. For all practical purposes it was not possible to manipulate the pictorial elements within individual frames. The usual culmination of photochemical film restoration project was a new film negative and new film positives created from that negative.

Many limitations of photochemical restoration vanished with the advent of digital imaging and digital manipulation technology. Not only can film materials now be digitally duplicated and edited, but it is also a simple matter to manipulate the image content within individual frames. Powerful tools provide film restorers with the ability to identify and thoughtfully remediate damage and deterioration suffered by the original material and to return the appearance of a film to a state closer to what it would have been when it was first created.

Unfortunately, these same powerful tools provide the ability to obliterate the character and integrity of the original film and to erase any vestige of aesthetic or historical veracity. Improperly or carelessly applied digital tools afford the means to distort, reinterpret, and misrepresent the aesthetics – and content – of the cultural and historical materials that archives and other collecting institutions are duty-bound to preserve.

This section concludes with an appendix detailing the ethical and pragmatic guidelines and rules – and the red lines – for digital film restoration projects.

MAINTAINING AUTHENTICITY AND THE ANALOGUE TO DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION

Digitisation of photochemical film transforms motion picture material from physical incarnation into a software-encoded approximation. It could be said that the simple act of digitising an analogue film produces a new and different object, thereby providing licence (or an excuse) to “modernise” its appearance or rationalise variance from the original. That would be an invalid – and unethical – interpretation.

While archives are the caretakers of the past, they also shape the future. As our analogue materials migrate into the digital realm, it becomes increasingly likely that these digital versions are the only ones that future generations will know. It is our responsibility to not only preserve the “content” of a film but also to preserve its nature. Every decision taken during the analogue-to-digital transformation, whether it is documented or not, will endure as perhaps the only accessible version of the film. Non-specialised audiences cannot be expected to understand the difference between categorisations such as “restoration” and “derivative work”. They will only know the version of the film that has been made accessible in its new digital incarnation.

This is why it is critical to define red lines and hard borders if we are to discuss the ethics of restoration. This is why the ethics of film restoration matter.

LEXICON

The means and terminology of photochemical film preservation, duplication, and restoration are generally well documented and understood.[2] The definitions that follow are intended to provide a similar foundation for the digital realm. As such, they necessarily overlap and include the essential preparatory activities such as historical research, philological studies, aesthetic analysis, and physical examination of the film and the materials that are common to both photochemical and digital projects.

Projects that transform photochemical film into digital renderings have varying goals and methodologies and, strictly speaking, not all of them are restorations. The following definitions should be not be rigidly interpreted since projects often include characteristics attributed to more than one category.

Photochemical Restoration: Physical reproduction of a film on the same medium, by photochemical duplication and printing, involving modern workflows similar to the historic original production methods.

Digital Workflow: The complete end-to-end process for analogue-to-digital conversion. This workflow typically includes digitisation (scanning), and export or rendering that creates a new instance of the film (either digital or analogue). This workflow optionally includes digital editing and/or digital image manipulation. The activities undertaken in this workflow are commonly shared by both Digital Reproduction and Digital Restoration.

Digital Reproduction: Using the digital workflow to create a digital copy of photochemical film material. The intent of the reproduction is to create an unmanipulated digital representation that appears as close as possible to the original film material.

Digital Restoration: Using the digital workflow to create a new representation of a specific film or object in a way that respects, to the greatest extent possible, the characteristics of the historical film. The process may make use of digital restoration tools to manipulate the scanned frames in order to remediate damage that has occurred to the physical film material. It may combine footage from multiple sources in order to create a more complete or higher-quality final result.

Reconstruction or Editorial Restoration: A film restoration may or may not include some amount of reconstruction. This could come through combining multiple film sources or through the creation of new material for insertion. Examples of this new material could be new titles that stand in for those missing from the surviving film material, or insertion of stills or text to bridge a missing portion of the film.

Derivative Work: We use the term Derivative Work to describe new film objects created through the appropriation and subsequent alteration of the original. Such works are not restorations because they do not attempt to restore the film to an original state. Giorgio Moroder’s altered version of Metropolis (1984) and Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old (2018) are derivative works despite marketing campaigns promoting them as “restorations”.

Digital Remastering: This term is often used by commercial marketing departments in an imprecise or even meaningless way to promote commercial motion-picture products (DVD, Blu-ray, online streaming, etc.). Though often advertised as “restorations”, these “remastered” editions often exceed the ethical limits described in this paper by altering essential characteristics of the original film (e.g., removing grain, changing aspect ratio, removing splices, etc.). In other cases, “digital remastering” merely consists of the Digital Reproduction defined above, or the careful creation of good quality, theatrical standard, digital masters.

THE DIGITAL RESTORATION WORKFLOW

Workflow planning for a digital project begins by defining the goals and purpose of the project. Is the purpose to simply create a digital reproduction of a single film element (Digital Reproduction)? Will it be a reconstruction and restoration of a film that survives only in multiple fragmentary sources (Digital Reconstruction and Restoration)? Or do the goals fall somewhere in between? Will the project culminate in a new 35mm negative and prints, or will the end product remain forever in the digital realm (DCP, etc.)? Determination of the project workflow depends on the answers to questions such as these.

Though project goals vary, a general outline for a project includes the following steps, some of which may be optional depending on your project goals.

- Project planning

- Research, material assembly

- Scanning/Digitisation

- Editing

- Digital intervention/Restoration

- Grading (timing)

- Export and Rendering

- Projection and Distribution

The following paragraphs describe and view these steps through the lens of film restoration ethics. Though the specific methodologies and technologies will evolve over time, these ethical principles should endure as reliable guideposts.

GOAL SETTING AND PROJECT PLANNING

Project planning is the essential first step before proceeding with a film restoration project. One of the most important aspects of this planning is for all project stakeholders to agree that the project will adhere to these ethical guidelines. This sounds easier than it may actually be, particularly if project stakeholders include commercial interests, collectors, or untrained personnel. It is also important to impress these guidelines on commercial service providers, such as film labs, that may not be accustomed to working to archival standards.

Project planning also includes deciding what form, or forms, the final restoration will take and what intermediate work products will be saved for archiving once the project is complete. At a minimum, the raw scans of all materials used in the restoration should be preserved. The original materials may not survive, or it may not be possible to reassemble them again if they have been collected from multiple sources. Keeping the raw scans serves as a critical safeguard that the best-available and most accurate, unmanipulated representation of the original materials is preserved.

RESEARCH AND MATERIALS

It is impossible to ethically restore a film without understanding the context and technology of its original production. Without such understanding there can be no historical basis for the decisions taken. If the restoration team has access to historically reliable reference prints, they should serve as guides to the restoration decisions throughout the entire process.

If a restoration is not based on, or does not have access to, original prints but instead relies on negatives or separate production elements, then having an understanding of the context, technology, and aesthetics of the original production is absolutely essential in achieving an accurate and ethical result.

Restoration Source Selection

Each project may have a range of source materials to work from, such as exhibition prints, duplicate negatives, fine grain positives, original camera negatives, small gauge reduction prints, later generation duplicate prints, magnetic media, etc. Careful selection of the materials, if you have a choice, will have a great influence on all the restoration decisions that follow.

Each type of material has advantages and disadvantages, and some require more intervention than others to achieve the desired result of reproducing an historically accurate release print. When choosing elements, it is important to understand the level of digital intervention required and weigh that against the quality of the element.

Camera Film Elements

It may seem counterintuitive, but original camera negatives may not be the most desirable source material for digital film restoration, especially when the final result will not be recorded back to photochemical film. High-resolution scans of camera negatives may produce the sharper image desired by commercial enterprises but are highly problematic from an ethical perspective. In addition to presenting an inauthentic look and sharpness, scanned camera negatives reveal details that were never visible in release prints, such as wires for special effects, blending of backgrounds, in-camera matte and bi-pack shots, settings, and painted scenery. Scanned camera negatives also do not include any artistic or technical processes that led to the finished release prints, and they lack the historical and aesthetic character of the film as it was originally presented.

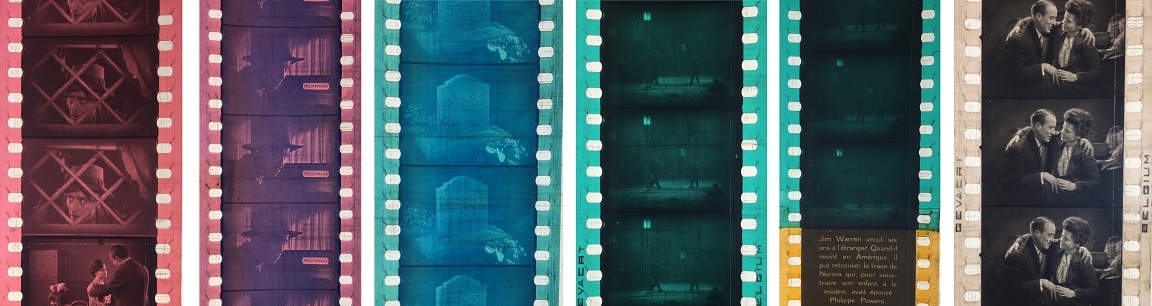

Conversely, distribution prints, if they are in good condition and of good photographic quality, have considerable advantages as source material since the print, or prints, possess characteristics not present in the negatives. These characteristics include film grain, colour grading,[3] applied colour systems (tinting, toning, stencil-colouring), aesthetics of particular film stocks, special effects compositing, optical effects, and other aesthetic and historical characteristics.

Opticals and Effects

The question of optical and special effects primarily becomes a concern when dealing with negatives or production materials where the effects are not already composited. Recreating effects such as cross-dissolves, fades, iris effects, double exposures, etc., using digital tools can result in a look very different from that provided by the original processes.

From an ethical perspective there is no question that the appearance of the original effect must be preserved. If possible, consider recreation through the original optical processes or substituting the effect from a print rather than attempting to digitally recreate an effect. If that is not possible, special care must be taken to recreate the appearance of the original effect with the goal of matching the original technology to the greatest extent possible, even if the effect could be digitally “improved”.

SCANNING AND DIGITISATION

The first step in commencing a digital workflow is converting (scanning) the analogue image media into a digital format. Because scanning and the associated technologies are addressed in The Digital Statement: Part I,[4] the discussion that follows is limited to scanning as it relates to film restoration ethics.

Generally speaking, the goal of scanning is to produce the closest possible digital approximation of the photochemical film element. For this reason, the film element should be scanned at the highest resolution available, practical, and affordable in any given situation.

Many film scanners offer the option of scanning with a wet-gate or diffuse light capability in order to minimise the appearance of scratches on the film base. These techniques can be highly beneficial and raise no ethical concerns if they are approached with caution. If you are considering wet-gate or diffuse light scanning for your project we recommend that you perform preliminary test scans and decide by examining the result.

Many scanners also offer facilities for “automatic” cleaning or “automatic restoration”. Capabilities such as these should be avoided since they lack the detailed curatorial control that can exerted during the Digital Intervention/Restoration phase.

Once scanning is complete, it is highly recommended that you backup and preserve the resulting data before proceeding further. This is not only essential in order to create a point of recovery in case of data loss later in the project, but it more importantly serves as a record of the unmanipulated image data. To a certain extent, and adhering to the principle of reversibility, preserving the raw scan is more important than preserving the completed restoration. It is possible to re-do a restoration, but you may never be able to re-capture a raw scan, especially in the case of rare or deteriorating materials.

DIGITAL INTERVENTION/RESTORATION

To many individuals, the purpose of digital restoration boils down to a technical process of “cleaning up” or even “improving” or “modernising” digitised film images. Accepting this oversimplified premise dismisses crucial ethical considerations and ignores completely the curatorial responsibilities of the restorer.

If the purpose of the project is Digital Restoration and not Digital Reproduction, then digital image-restoration techniques may be engaged to remove damage that has occurred to the original film material. Generally speaking, the areas that may be ethically addressed are characterised as damage to a print, such as dirt and scratches, that occurred during its circulation, and damage (or subsequent repair) that was imposed during the life of the material. What may not be “corrected” or addressed are characteristics that are genuine to the original, such as properties of the original photography (e.g., camera instability or wobble), original negative and print assembly (splice lines), even original production mistakes such gate hairs in the camera recorded on the negative, as well as other original characteristics of the technology or production processes, such as film grain and film processing/developing marks.

See the appendix, “Digital Tools and Film Restoration Ethics”, for detailed discussion of the ethical considerations as they relate to specific image-manipulation techniques and scenarios.

GRADING (TIMING)

Restoring or reproducing the characteristics of a film’s original colour is an essential aspect of ethical film restoration. For a digital restoration, this can be particularly challenging since current film-scanning technology often does not accurately capture the colours of the original.

The most important element of accurate colour grading is to work with reference materials that provide objective bases for comparison. The ideal references are exhibition prints dating from the time of the film’s original release, though it is important to understand that no single print from the time of the film's exploitation is necessarily definitive. It is not uncommon for contemporary prints to exhibit variance in grading or colour, particularly in the case of colour processes whose results were not regular, such as tinting or Technicolor.

If original or unfaded materials are not available, research, reference, and professional judgement should be your guide. Options include:

- Comparison with prints made at the time of the original release. Subsequent re-releases or duplication may exhibit different characteristics than original prints from the time of release.

- Comparison with similar films created with similar technologies. Different colour systems each have their own look. Be aware of the characteristics and limitations inherent in the film stocks and chemistry used at the time of production. If you do not have an exact reference for the title you are restoring, perhaps a similar film (same studio, same era, same genre, same film stock, chemistry, and technical specifications) can provide useful guidance.

- For silent films that are known to be tinted and/or toned, use films from the same era and studio for colour reference. If no information on the original colouring is available, it is better to leave the film uncoloured than to guess at what the colours might have been.

- For more recent films where the filmmakers or crew members are still living, it may be possible to have them observe or participate in the grading. In such a case, it is incumbent on the restorer to ensure that the director or cinematographer does not indulge in updating or revising the look of the film.

Correcting or re-creating applied colours of the silent era can pose unique challenges, particularly since current scanning technology often does not accurately capture colour from tinted, toned, or hand- or stencil-coloured material. One approach is to discard the original colour data, and then use digital grading tools to recreate the original tints and tones. Another less commonly employed technique is to retain the colour captured by the scan, imperfect though it may be, and use digital grading tools to adjust the colour to an approximation of the original.

For projects that will be printed back to 35mm film there are two additional solutions. The most common is to recreate tinting and toning on colour stock. Another approach used by several archives is to produce a new 35mm black & white print and then engage specialists to chemically tone and/or dye-tint to match the original.

Scans of stencil or hand-coloured prints can exhibit the same problems of colour reproduction as tinted and toned prints. This can prove to be challenging since the colours cannot simply be recreated as in the case of tinting and toning. For these films it may be necessary to carefully adjust the colours using grading and colour-timing software.

EXPORT AND RENDERING

It should go without saying that all films that are digitised, manipulated, or rendered for digital presentation – just as with photochemical reproduction – must retain their original characteristics, including frame rate and aspect ratio.

Aspect Ratio (digital)

Just as with frame rates, all films should be digitised, preserved, and presented in their original aspect ratio. In instances where the digital aspect ratio does not support the exact dimensions of the original material, letterboxing or pillar-boxing with a black matte is the only acceptable solution. The film image should never be cropped, stretched, compressed, zoomed, or reframed (“pan and scan”).[5] Never. Never ever.

Aspect Ratio (analogue film)

If the end result of a restoration is to be a new film negative, it is essential to record the entire film frame, without cropping, back onto the negative film stock. During projection, the image will generally be framed by the projector gate but the film material itself should always contain all the image information that was present in the original.

Frame Rates

No matter the format, digital rendering must always reproduce a film’s original frame rate. This is generally a simple matter, but it presents a challenge when it comes to films of the silent era because of the current limitations of digital projection technology. At the time of writing, digital projection is limited to a very small number of supported frame rates,[6] the most commonly used being 24fps.

Currently the only way to digitally project a non-24fps film at its original frame rate is to manipulate the number of distinct frames that are projected. Typically, the desired frame rate is lower than the now-standard 24fps, with ranges of 16-22fps being the most common. Though unsatisfactory, the current approach is to “stretch” these slower films by periodically duplicating frames so that the correct number of individual frames is projected per second. In some cases, an alternative approach might be to cleverly take advantage of higher DCP frame rates. If the original frame rate of the film can be doubled or tripled to match a supported DCP frame rate, then, equally, doubling or tripling all the frames in a digital rendering can achieve the purpose of presenting all frames for an equal and appropriate duration.

Periodic duplication of frames has the advantage of not introducing any non-historical image information but can lead to a visibly jerky motion. To artificially address this issue there are algorithms that can create additional frames by blending authentic frames to derive and insert new frames through motion interpolation. This computer-generated imagery is ethically problematic, and must be avoided, since it creates frames that historically never existed. Generally speaking, it doesn’t work very well either.

These crude workarounds to overcome the inadequacies of digital projection are currently an unfortunate reality. More essential is a collaboration between industry and the archive community to implement flexibility and support for heritage frame rates in digital projection.

EXHIBITION AND PROJECTION

Closely related to Export and Rendering is the final step in any restoration: Exhibition and Projection. Because the technical aspects of projection are exhaustively covered in FIAF publications FIAF Digital Projection Guide[7] and The Advanced Projection Manual,[8] the discussion here is confined to ethical concerns.

Since the goal of restoration is to faithfully reproduce, or approximate, the character, appearance, and aesthetics of the original, the practice of projection and exhibition must serve the same objective. Digital projection or dissemination must always respect the original aspect ratio, and photochemical film prints must be presented at their original frame rates. Projection apparatus should also be prepared and calibrated to accurately reproduce the colours as they were fixed during the grading process.

CONCLUSION

With the wide availability and relatively low cost of digital imaging technologies, archives and audio-visual heritage institutions now have increasingly powerful tools for rehabilitating, restoring, and providing access to the materials in their care. Unlike commercial companies, these institutions have an additional ethical mandate: the task to preserve and present an historical and aesthetically accurate reproduction of the film. Creating new or "modernised" versions, corresponding to commercial criteria or based on the aesthetics or technical possibilities of current digital technology, is not the purpose of an ethical restoration. Most viewers will not be able to discern the changes that have been made; they will only know the version of the film that has been made accessible to them in the new digital incarnation.

Digital technology continues to evolve, and certain aspects of this paper will eventually become obsolete, but the underlying philosophy and principles of ethical film restoration will remain. Along with sufficient historical research, archives should be able to feel supported by these ethical principles when making complex decisions about their restorations.

APPENDIX: DIGITAL TOOLS AND FILM RESTORATION ETHICS

All film restoration projects are different. The type, quality, and era of the original materials vary, as do the goals that the projects hope to achieve. In some instances, it may be reasonable to employ a certain digital tool or technique where the same technique in a different situation could be completely inappropriate. The purpose of this Appendix is to provide a graduated set of pragmatic rules and ethical guidelines that should be considered in any restoration project. These rules are divided into the following categories:

Rule: Common and general usage rules as applied to digital restoration tools and techniques.

Guideline: Tools and techniques that may be open to interpretation or adapted to the purposes of the project.

Red Line: Tools or techniques that, without exception, exceed the bounds of restoration ethics.

RULES

These are the general rules as applied to digital restoration tools and techniques. In the absence of extenuating circumstances, these rules should always be observed and applied.

- The original editing of the version chosen for the restoration must be preserved. Re-editing, rearranging, adding or removing shots or titles, or "correcting" continuity is not permitted. In a case where multiple versions of a film may exist, for example domestic and export versions, re-releases, etc., the goal of the project should be to restore specific historical versions and not to create an ahistorical hybrid from multiple versions.

- The content and location of the original titles, as far as they are known, must be preserved. If original titles are not available, reconstructed titles must indicate they are modern reproductions.

- The original aspect ratio of the frame must be preserved. When scanning original material, the entire image for each frame must be captured without cropping. When restoring, the entire frame must be restored and subsequently recorded back to the new negative or digital rendering. In the case of rendering analogue films for digital projection, it is expected that cropping should be done at the frame edges to replicate the framing that would occur with analogue film projection masking.

- The original frame rate, or rates, of the film must be preserved. If the new restoration is printed back to film, the new copy must contain only the original frame-for-frame sequences, and the film should subsequently be projected at the original frame rate. In the more likely scenario of digital rendering and projection, the digital rendering (DCP, ProRes, etc.) must be prepared in such a way that the film is presented at the original frame rate (or a simulation thereof if digital projection does not support the actual original frame rate).

- The colour, contrast, and grading (timing) of the original must be respected. When possible, original reference prints from the time of production should be consulted in order to accurately reproduce the grading.

- All characteristics and artefacts of the film’s original manufacture, present in the negative or a first-generation print, must be retained. Examples of such marks and artefacts include:

- Film grain

- Splices between shots and titles

- Splices present in the original print, such as cuts creating special effects

- Dot lines (“string of pearls”) from developing racks

- Camera hair present in the original negative

- Flicker or density pumping (except flicker due to fading/aging)

- Tax, censor, and customs marks

- Camera instability (not instability as a result of duplication)

- Characteristics of original effects, such as density changes during optical effects and transitions

- Electrostatic marks present from the negative

- The above list notwithstanding, it is often the case that film restorations are based on later-generation materials that include damage suffered over the life of the film or through the result of poorly executed laboratory reproduction. In such cases it is permitted to address problems introduced through duplication, such as:

- Gate hairs printed in during duplication (not original camera hairs)

- Instability introduced during duplication (not original camera wobble or instability)

- Splices that repair torn frames (not original splices from the production or manufacture)

- Splices are an area of special consideration. Not only can splices, such as those between shots and titles or those between differently coloured segments in silent films, be original marks from a film’s production, they can also present clues and historical markers. In early films, splices are often historical as well as artistic features, for example, those that create the magical, transforming jump-cuts in the films of Georges Méliès. Splices in a print can also indicate where a shot has been removed, where a title was changed, or where a censor required a cut. Because of this it is critical to consider digitally removing a splice only when it is abundantly obvious that a splice is simply a repair, such as a taped splice across the middle of a frame.

- Finally, the one area that must be addressed is that of defects and imperfections – instability and frame deformation not present in the original film source, for instance – introduced during the scanning and digitisation process.

GUIDELINES

Tools and techniques that may be open to interpretation or adapted to the purposes of the project.

- Cue marks present in the negative should be preserved. Also, cue marks were often (and still are) typically scratched or punched into the end of film reels throughout the life of a print. Projection cue marks are latter-day damage that can be removed, and it is equally valid to consider them to be evidence of the life of the object. These projectionist’s cue marks (added after a film’s release) are left to the restorer’s discretion.

- It is permissible to remove traces of repairs (tape, glue, etc.) and marks due to handling and projection of the print (fingerprints, hair, squashed insects, staples, etc.).

- Traces of material decomposition may be confidently repaired if that can be done without altering the content or characteristics of the original and without crossing any of the Red Lines described in the section below.

- Films that are tinted should be scanned with the tinting to retain whatever tinting information is present, even if the colour is degraded or faded. This does not preclude the option to recreate applied colours (tinting and toning) in order to achieve a result that more accurately reflects the original film colouring.

- Though this must be approached with extreme caution, recompositing shots by blending multiple sources can be done to recreate damaged opticals or to combine elements from different-quality film sources. This very invasive technique should only be considered if the materials used for recompositing can be taken exclusively from materials contemporary with the production itself, not anachronistic or invented sources, and if digital tools are used to approximate the original to the greatest extent possible.

RED LINES

The following techniques exceed the bounds of restoration ethics and should not be employed under any circumstances.

- Colourising, the process of artificially adding colour to film materials that were originally produced and distributed in black & white. Colourising is an act of vandalism and has no place in ethical film restoration.

- Creating entirely new frames through the use of interpolation. This technique is sometimes suggested to create a new frame in order to bridge a gap or jump-cut caused by what is presumed to be a missing frame. Interpolated frames can also be inserted as a speed-correction in an attempt to overcome the inadequacies of digital projection. For whatever reason, this technique creates an ahistorical film frame that never existed. It may also erase historical evidence of manipulation of the original artefact (e.g., editing, censor cut, removed title, etc.)

- Using a painting or drawing tool to draw or fill in missing parts of an image. These crude tools are strictly additive and do not engage any contextual information from a frame or from adjacent frames.

- Artificial “sharpening”, “smoothing”, and “enhancement”. One unfortunate side-effect of media advertising is that many people now consider image sharpness and image quality to be synonymous. To deliver what is perceived as a sharper or “modernised” image, many digital restoration suites include a Sharpness tool that artificially sharpens or smooths edges and increases contrast to elements within the frame image. Rather than correcting or restoring, these tools distort the original image, and their use is incompatible with ethical restoration practice.

- “Grain management” is the generic term for reducing or eliminating film grain or, conversely, adding synthetic film grain. Both techniques should be shunned. The original film grain inherent in the original film material is to be respected at all times. Some commercial restoration practices employ a process whereby film grain is digitally removed, the film is digitally “cleaned” using automatic processes, and then synthetic film grain is applied to give the result a “film look” that conveniently also conceals artefacts introduced by the automatic cleaning process.

Endnotes

[1] The authors recognise that the words “ethics” and “ethical” can be problematic. These loaded terms carry subtext that can introduce emotional and defensive responses into what should be rational technical and aesthetic discussions. We strongly emphasise that within the context of film restoration, the terms “ethics” and “ethical” are not intended as a measure of an individual’s, an organisation’s, or a project’s morality, honesty, integrity, or virtue, but should more reasonably be interpreted as technical and curatorial standards, principles, models, and ideals.

[2] For further reading on photochemical film restoration, consider Restoration of Motion Picture Film by Paul Read and Mark-Paul Meyer, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000.

[3] It should be noted that the digitisation of these colours is not without technical limitations, as described in the chapter on the technical characteristics of the scan (Digital statement II). It is often necessary to re-grade the elements, while referencing an original print or other appropriate colour reference.

[4] The Digital Statement: Recommendations for digitization, restoration, digital preservation and access. <https://www.fiafnet.org/pages/E-Resources/Digital-Statement.html>.

[5] Pan and scan is the method of adjusting widescreen film images so that they can be shown in full-screen proportions of a standard definition 4:3 aspect, often cropping off the sides of the original widescreen image to focus on the composition's most important aspects.

[6] The current SMPTE standard for digital projection allows for rates of: 24, 25, 30, 48, 50, and 60 frames per second. Also note SMPTE standard ST 428-21:2011 - SMPTE Standard - Archive Frame Rates for D-Cinema, <https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7291863>.

[7] Torkell Sætervadet, FIAF Digital Projection Guide, Brussels: FIAF, 2012.

[8] Torkell Sætervadet, The Advanced Projection Manual, Brussels, Oslo: FIAF/Norsk Filminstitutt, 2005.